Caching Options in an Elixir Application

Are you overworking your database? Are you paying for each query? Are you returning the same payloads again and again? It might be time to think about caching and Elixir and Erlang make this easy with several in memory options. I learned about the 2 Erlang options at ElixirConf 2019 and felt compelled to write this post, so a big thank you to all those who shared!

There are four different standard methods for temporarily storing and accessing data in a simple Elixir application. This article compares those methods, provides usage examples, and offers my personal opinion on when to use each tool. Here are those 4 simple strategies of storing data for quicker retrieval than going to a database:

- Using

Agent - Using

GenServer - Using

:ets(Erlang Term Storage) - Using

:persistent_term

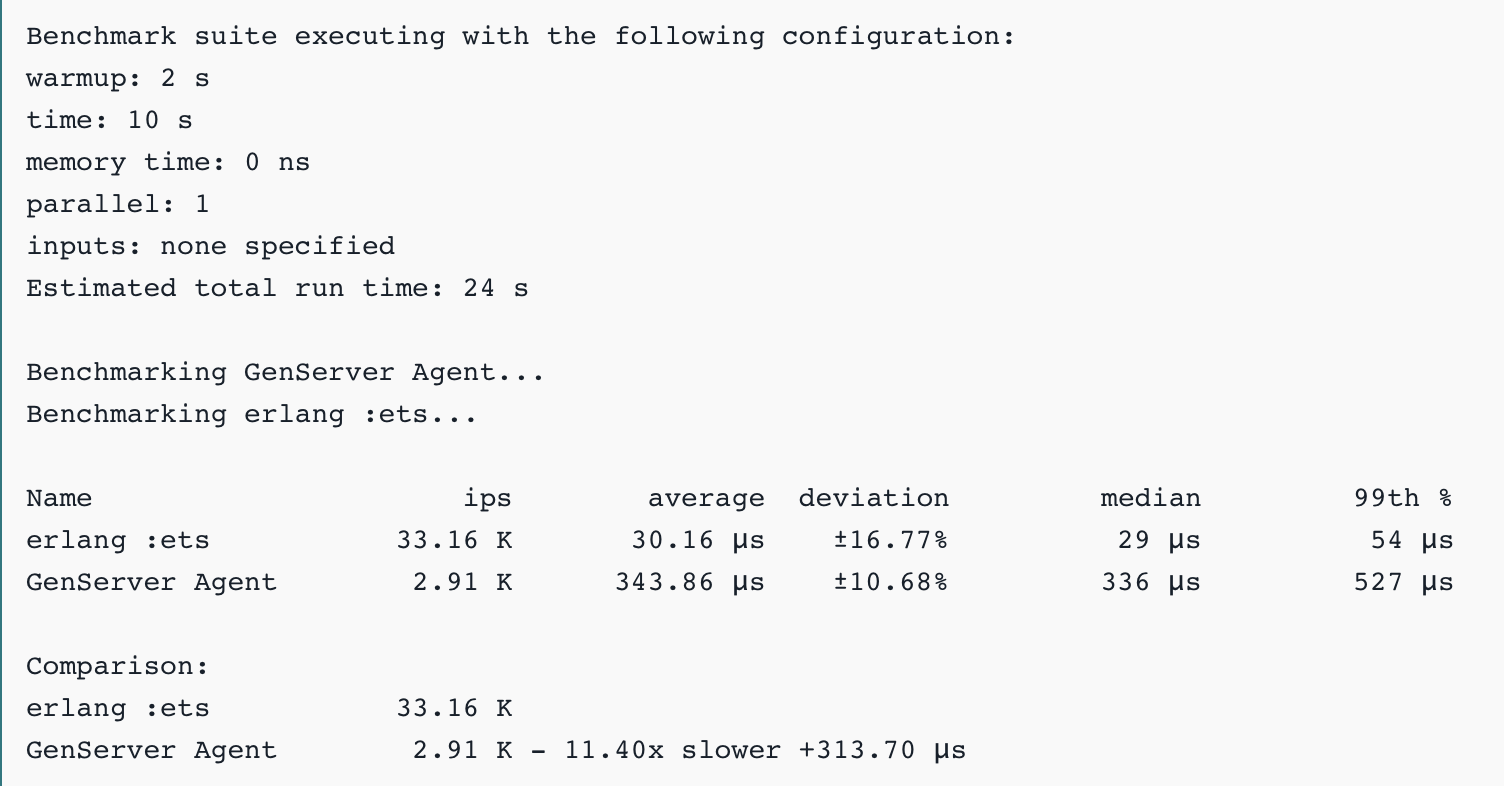

If you wonder why this matters, here is a benchmarking test comparing the time it create a table, set 100 key value pairs, and remove 100 key value pairs. The results show that :ets is significantly faster than Agent (and therefore GenServer).

Using Agent

Example:

Agent.start_link(fn -> %{} end, name: :us_state_abbreviations)

-> {:ok, #PID<0.102.0>}

# or to clarify the first argument and show a namespace error

initial_state_callback = fn -> %{}

Agent.start_link(intial_state_callback, name: :us_state_abbreviations)

-> {:error, {:already_started, #PID<0.102.0>}}

# Accessing all Agent data

Agent.get(:us_state_abbreviations, &(&1))

-> %{}

# Checking for a certain value, in the lookup

key = "OH"

Agent.get(:us_state_abbreviations, fn(states) -> Map.get(states, key, "N/A") end)

-> "N/A"

# Updating Agent data

updated_state = %{"OH" => "Ohio"}

Agent.update(:us_state_abbreviations, fn(_) -> updated_state end)

-> :ok

# Confirming the updates

key = "OH"

Agent.get(:us_state_abbreviations, fn(states) -> Map.get(states, key, "N/A") end)

-> "Ohio"

Pros: Agent can be accessed from anywhere in the application, provided the requester has the name used to register Agent. If a single process crashes, Agent state persists. Agent is very lightweight to implement and use.

Cons: If your entire application crashes, Agent state is lost.

Opinion: In most cases, Agent is reimplementing given behaviors of GenServer state management. If you find yourself sharing cached data between modules of your application, that is a sign of an architecture design problem. Agent under the hood is a simple GenServer you don’t manage, so in most situations, it is better to build your own.

Using GenServer

Example: I am not going to rewrite the hex documentation, so please look here(https://hexdocs.pm/elixir/GenServer.html) for information about GenServers. The quick summary is that GenServers maintain state through their return values, and each function called through a handle_cast, handle_call, or handle_info includes the current state as an input. A queue of internal messages is maintained, and the state updates sequentially as the servers process this call stack.

Pros: GenServers easily integrate into your supervision tree, with built-in hooks to manage and recover state. If you need to consume data from a GenServer elsewhere in your application, you implement accessor methods on the GenServer.

Cons: Requires more direct and considered state management, meaning more work to set-up, configure, and test your module.

Opinion: Leaning on GenServers for caching, recovering, and managing state is the best method for caching in Elixir. While it does feel like more work is required, this work gives the additional control developers need to lock down their data flows.

Using :ets

Example:

# create a lookup table

:ets.new(:us_state_abbreviations, [:set, :public, :named_table])

-> table_ref

# lookup a value when it doesn't exist

:ets.lookup(state.table_ref, key)

-> []

# lookup when it does

-> [{key, value}, ...]

# how to handle these responses

def lookup(module \\ __MODULE__, key) do

GenServer.call(module, {:lookup, key})

end

def handle_call({:lookup, key}, _from, state) do

# good practice to save the ets table ref in state

case :ets.lookup(state.table_ref, key) do

# match against key for corelated value

[{^key, value}] -> {:reply, {:ok, value}, data}

[] -> {:reply, {:error, :not_found}, data}

end

end

# insert a record

:ets.insert(state.table_ref, {key, value})

-> true

# nuke table

:ets.delete_all_objects(state.table_ref)

-> true

Pros: Persists past process crash, but not past an application crash. Fast reads, fast writes. It is a simple key-value store of tuples ({key, value}).

Cons: Requires more parsing of responses. Less flexible lookup. There are extensions for :ets which allow for searching by Ecto structs which I will post about in the future.

Opinion: For most applications, using GenServers is sufficient for performance. Often, GenServer state contains business logic, and the :ets state contains distilled information for external consumption. I think of this as the external cache whereas the GenServer state is primarily an internal cache. A typical pattern is attaching these returned table references to a GenServer state.

Using :persisent_term (available in erlang 22)

Example:

:persistent_term.put("OH", "Ohio")

-> :ok

:persistent_term.get("OH")

-> "Ohio"

Pros: :persistent_term has much faster read times, even than :ets. Data persists past an application crash, meaning it is an ideal place for certain nuggets of information. Shared across all nodes in a cluster.

Cons: Slow write times since updates sync across all nodes.

Opinion: I haven’t found the right use for this yet in any of my applications, but it seems useful for isolated problems at scale.

Summary

In summary, you should probably use GenServers instead of Agent in most situations. Agent is a lazier GenServer with more default behaviors. For performance and flexibility, use both :ets and a GenServer. In GenServer state, store a reference to :ets tables and use GenServer calls to lookup against this table because :ets is more performant. If you are operating a cluster, and aren’t updating these read values as frequently, consider using :persistent_term. It updates across all connected nodes in a cluster (using a HashRing library like ExHashRing), so while this is powerful, it is also expensive to write data through this system. Read of this data is faster, and more persistent, than even an erlang call like :ets.

prying.io

prying.io